LAS VEGAS — For Americans with food allergies, label reading is a way of life. And for commercial baking companies, the term “Top 8” — referring to allergens — is quite the same. So, when the FASTER Act was signed into law in April to recognize sesame as the ninth allergen on the list, those in both camps took notice.

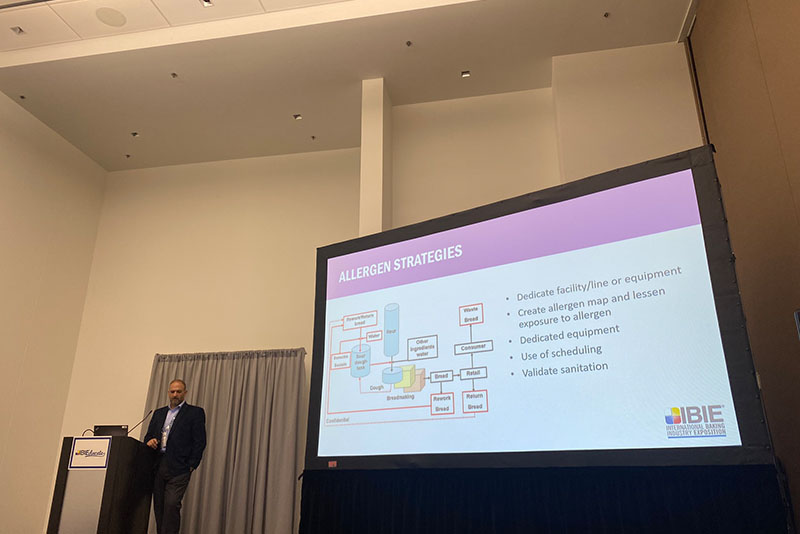

During the International Baking Industry Exposition (IBIE) — which took place Sept. 18-21 in Las Vegas — Nathan Mirdamadi, senior food specialist for Commercial Food Sanitation, addressed the operational implications of understanding and managing the risks associated with producing baked goods with sesame.

When it comes to recalls for American food manufacturing, nearly a third of food allergy recalls were initiated from bakeries, many of which were due to labeling issues or omission.

“Those of us who work in food manufacturing know that the labeling aspect of [food allergens] is problematic,” Mirdamadi said. “The entire intent of the law was to inform consumers. But I also think we’ve learned that labeling — and controlling labels — is not nearly as easy as we had hoped.”

While some food manufacturers rely on precautionary or defensive labeling, Mirdamadi warned that not only is such reliance insufficient, but it also does little to reduce liability.

Across an entire grocery store, roughly 6% of all products contain sesame.

“That’s much higher than I think people appreciate,” Mirdamadi said, noting that other allergens such as tree nuts, which can garner a similar reaction in terms of severity, looks more like 3% of total grocery.

But addressing sesame as the ninth allergen in some ways introduces just as many questions as answers. For Mirdamadi, the safest protocols begin proactively, not defensively.

In looking at how sesame is used in baked goods specifically, it’s often applied topically to a product post-bake, such as with hamburger buns. Because it’s a very fine particulate used as more of a topping than inclusion, controlling sesame as an allergen is like “trying to remove sand from the beach,” according to Mirdamadi, especially when most post-oven equipment sanitation employs dry methods.

“It’s a very serious challenge,” he said. “Then we take into consideration supply chain issues and sanitation departments struggling to find, train and retain employees. We’re pushing ourselves into a corner trying to create a scenario where we can successfully remove sesame.”

Some manufacturers are developing a brush with vacuum attachments that can minimize the migration of seeds. Other technologies include driving belts from the edge rather than the center shaft to eliminate transfer points on the line.

Some manufacturers are developing a brush with vacuum attachments that can minimize the migration of seeds. Other technologies include driving belts from the edge rather than the center shaft to eliminate transfer points on the line.